The history of France and the United States is bound by an ancient and blood-forged friendship, one that predates the very existence of the American republic. While names like George Washington and Thomas Jefferson are etched into the bedrock of American history, there is one figure who bridges the gap between the Old World and the New: Gilbert du Motier, Marquis de Lafayette.

For international students, expatriates in Paris, and lovers of french civilization, understanding Lafayette is essential. He is not merely a historical figure; he is a symbol of the Enlightenment ideals that fueled revolutions on both sides of the Atlantic. To study his life is to study the very essence of French history.

This article explores the genesis of the Franco-American alliance and the pivotal role played by this young French aristocrat who became a hero of two worlds.

The genesis of an unlikely alliance

To understand Lafayette’s journey, one must first understand the geopolitical climate of the late 18th century. Following the Seven Years’ War, France had lost much of its North American territory to Great Britain. The sting of defeat was fresh in the halls of Versailles. When the thirteen American colonies rebelled against the British Crown, France saw an opportunity not only to weaken its rival but to embrace the burgeoning ideals of liberty.

However, the alliance was not immediate. It began with covert aid orchestrated by the playwright Pierre-Augustin Caron de Beaumarchais and the diplomat the Comte de Vergennes. It was the persuasion of American envoys like Benjamin Franklin, who charmed the French salons, that eventually turned the tide. Yet, before the official Treaty of Alliance in 1778, individual French officers, driven by the spirit of the “Lumières” (Enlightenment), took it upon themselves to fight for the American cause. Foremost among them was a nineteen-year-old orphan of immense wealth: Lafayette.

The arrival of the “hero of two worlds”

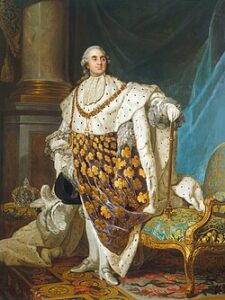

In defiance of King Louis XVI, who explicitly forbade his departure to avoid an early diplomatic crisis with Britain, Lafayette purchased his own ship, La Victoire. He set sail for the Americas, leaving behind his pregnant wife and his privileged life at the French court.

On June 13, 1777, the Marquis de Lafayette arrived on the coast of South Carolina. His arrival was met with initial skepticism; the Continental Congress was weary of foreign officers demanding high ranks and pay. However, Lafayette was different. He offered to serve at his own expense and initially as a volunteer. Impressed by his humility and zeal, Congress commissioned him as a Major General in the Continental Army.

The bond with Washington

Lafayette’s meeting with George Washington changed the course of his life. Despite the age difference and the language barrier, a bond formed almost instantly. Washington, who had no biological children of his own, came to view the young Frenchman as an adopted son. For Lafayette, who had lost his father in battle at the age of two, Washington became the father figure he never had. This relationship became the emotional core of the Franco-American alliance.

Blood and glory: Lafayette in combat

Lafayette did not come to America merely to observe. He came to fight. His baptism by fire occurred at the BATTLE OF BRANDYWINE in September 1777.

During the chaotic retreat of the American forces, Lafayette displayed immense courage. While rallying the troops to maintain order, he was shot in the leg. Despite the wound, he refused to leave the field until a structured retreat was organized. This act of bravery cemented his status among the American soldiers. He was no longer just a wealthy French aristocrat; he was a brother-in-arms who bled for their liberty.

Following his recovery, he shared the hardships of the winter at Valley Forge, using his own fortune to purchase supplies for the freezing, starving troops. His military acumen grew, and he later led troops with distinction at the Battle of Rhode Island and in skirmishes in Virginia.

The diplomatic mission: securing Louis XVI’s support

By 1779, the war had reached a stalemate. The Americans needed more than just volunteers; they needed the full might of the French military machine. Realizing he could do more for Washington in Versailles than on the battlefield, Lafayette requested a leave of absence to return to France.

His return was a triumph. Although technically under arrest for disobeying the King in 1777, he was quickly forgiven. Capitalizing on his newfound fame, Lafayette lobbied Louis XVI and his ministers relentlessly. He argued that with naval support and an expeditionary force, Britain could be defeated.

His efforts, combined with the diplomatic work of Franklin, bore fruit. The King approved the “Expédition Particulière.” In 1780, Lafayette sailed back to America aboard the frigate Hermione, carrying the news that General Rochambeau was following with 6,000 French troops and a fleet of warships.

The road to victory: the convergence at Yorktown

The climax of the American Revolution is a testament to the necessity of the French alliance. By 1781, British General Lord Cornwallis had entrenched his army at Yorktown, Virginia, awaiting supplies from the Royal Navy.

Lafayette, commanding a small division of light infantry, played a crucial game of cat-and-mouse with Cornwallis, trapping him in Yorktown and cutting off his escape routes by land. Meanwhile, the grand strategy involving the combined forces unfolded:

- Rochambeau and Washington marched their combined armies south from New York.

- Admiral de Grasse, commanding the French fleet, arrived at the Chesapeake Bay. In the decisive Battle of the Capes, De Grasse defeated the British navy, severing Cornwallis’s maritime lifeline.

- The siege: With the British trapped by Lafayette and Rochambeau on land and De Grasse at sea, the allied forces pounded Yorktown.

The force combined of Americans and French practically guaranteed victory against Great Britain. France contributed successfully to the American victory, managing to expel the British and obtain the recognition of independence thanks to the intervention of Rochambeau, de La Fayette, de Grasse, and the naval strategist Suffren (who fought the British elsewhere, stretching their empire).

On October 19, 1781, Cornwallis surrendered. As the British troops laid down their arms, the band reportedly played “The World Turned Upside Down.” Indeed, it had. The oldest monarchy in Europe had helped birth the world’s newest republic.

Lafayette and the spirit of french civilization

The story of Lafayette is not just a military history; it is a lesson in French civilization. It highlights a pivotal moment when French culture, philosophy, and military science intersected with American pragmatism and drive for independence.

For students and expatriates living in Paris, traces of this history are everywhere—from the statue of Washington at Place d’Iéna to the grave of Lafayette at Picpus Cemetery, where an American flag has flown without interruption since his death, even during the Nazi occupation of Paris.

Lafayette embodies the universal values that the Cours de Civilisation Française de la Sorbonne (CCFS) strives to teach. He represents curiosity, the courage to engage with foreign cultures, and the mastery of language and diplomacy to effect change.

Conclusion

The Marquis de Lafayette’s epic journey from the opulent salons of France to the rugged battlefields of America is a reminder of the enduring power of cross-cultural exchange. He did not just fight for a piece of land; he fought for an idea.

Today, as you walk the streets of Paris or study the intricacies of the French language, remember that you are participating in the same tradition of cultural exchange that Lafayette championed over two centuries ago. Whether you are a beginner looking to learn the basics or a scholar deepening your knowledge of history, the study of French civilization opens doors to understanding the world’s most pivotal moments.

Immerse yourself in french history and culture

Are you ready to deepen your understanding of French history, language, and culture? Join the Cours de Civilisation Française de la Sorbonne and walk in the footsteps of history.

Discover our French Civilization Courses