The cathedral builders: how France invented gothic architecture

Stand inside the nave of Chartres Cathedral on a summer afternoon. Watch as the light pours through the great rose window, flooding the stone floor with pools of sapphire, ruby, and emerald. Look up impossibly far up to the vaulted ceiling that seems to dissolve into the heavens. In that moment, you are experiencing exactly what the medieval builders intended: a vision of paradise made tangible in stone and glass.

Gothic architecture is arguably France’s greatest gift to the visual arts. Born in the Île-de-France in the mid-twelfth century, it spread across Europe with astonishing speed, transforming skylines from Portugal to Poland, from England to the Holy Land. But this was no gradual evolution it was a revolution, and it began with one man’s audacious idea in a modest abbey north of Paris.

Abbot Suger and the light of Saint-Denis

The story of Gothic architecture begins around 1137, in the royal abbey of Saint-Denis, the burial place of French kings. Its abbot, Suger, was one of the most remarkable figures of the twelfth century a man of humble origins who became the chief advisor to two kings and, in Louis VII’s absence on crusade, regent of France.

But Suger’s most enduring legacy was architectural. He wanted to rebuild his abbey church, and he had a theological vision to guide him. Drawing on the writings of Pseudo-Dionysius the Areopagite a mystic theologian whose works had been translated at Saint-Denis itself Suger believed that material beauty could lead the soul toward God. Light, in particular, was divine. The more light that could enter a church, the closer its worshippers would be to the divine presence.

The technical revolution

This theological impulse drove a series of engineering innovations that, taken together, constituted a new architectural language. Suger’s master builders whose names are lost to history combined three existing techniques in a radical new synthesis:

– The pointed arch, which distributed weight more efficiently than the rounded Roman arch, allowing for taller, more flexible openings.

– The ribbed vault, a skeleton of stone ribs that channeled the ceiling’s weight downward to specific points rather than along entire walls.

– The flying buttress, an external support structure that transferred the lateral thrust of the vault away from the walls, allowing them to be thinner and filled with glass.

The result was revolutionary. Walls that had been thick, fortress-like barriers became skeletal frames for enormous stained-glass windows. The interior of Suger’s new choir at Saint-Denis, consecrated in 1144, was flooded with colored light in a way no building had ever achieved before.

The effect on contemporaries was electrifying. Bishops and abbots from across northern France attended the consecration and returned home burning with the desire to build something similar. The race to the sky had begun.

The great cathedrals: a century of ambition

What followed was one of the most extraordinary building campaigns in human history. In the space of roughly a century from about 1140 to 1260 dozens of cathedrals rose across northern France, each more ambitious than the last. This was not merely construction; it was a competition, a collective act of faith, and a demonstration of civic pride.

Sens and Noyon: the first experiments

The Cathedral of Sens (begun c. 1135) is often considered the first truly Gothic cathedral, its design predating even Suger’s work at Saint-Denis. Noyon (begun c. 1150) followed, experimenting with four-story elevations and innovative vaulting patterns. These early Gothic buildings were still finding their vocabulary, but the direction was unmistakable: higher, lighter, brighter.

Laon and Paris: reaching for the sky

The Cathedral of Laon (begun c. 1155) introduced a dramatic five-tower silhouette and a four-story interior elevation that became a model for subsequent buildings. Its carved oxen peering from the towers commemorate the animals that hauled stone up the steep hill a touching tribute to the sheer physical labor behind these monuments.

Then came Notre-Dame de Paris. Begun in 1163 under Bishop Maurice de Sully, it was the most ambitious Gothic project yet attempted. Its nave reached 33 meters a staggering height for the time and its flying buttresses, added in the early thirteenth century, became iconic. Notre-Dame was not just a church; it was a statement. Paris was the capital of the French kingdom, and its cathedral would be the greatest in Christendom.

Chartres: the perfection of gothic

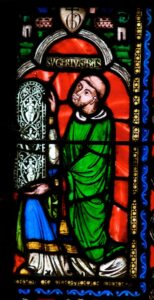

If Notre-Dame was ambition, Chartres (rebuilt after a fire in 1194) was perfection. The Cathedral of Chartres achieved what Gothic builders had been striving toward: a harmonious balance of height, light, and structural elegance. Its three-story elevation arcade, triforium, and clerestory — became the definitive Gothic formula. Its stained-glass windows, 176 of which survive from the thirteenth century, represent the most complete medieval glazing program in existence.

Chartres also preserves its original sculptural program: the Royal Portal on the west façade, with its elongated, column-like figures, represents a revolution in medieval sculpture, moving toward a naturalism that would flower in the coming decades.

Reims and Amiens: the coronation and the climax

The Cathedral of Reims (begun 1211) held a unique status: it was the coronation church of the French kings. Every monarch from Louis VIII to Charles X was crowned within its walls. Its west façade, adorned with over 2,300 sculptures — including the famous “Smiling Angel” is one of the supreme achievements of medieval art.

Amiens (begun 1220) pushed the Gothic envelope to its limits. Its nave vault reaches 42.3 meters, the tallest of any completed French Gothic cathedral. The building’s volume is so vast that it could contain Notre-Dame de Paris within it. Amiens represents the climax of the Gothic ambition: the maximum height and light that medieval engineering could achieve.

Beauvais: the dream that went too far

The story of Gothic ambition has a cautionary coda. The Cathedral of Beauvais, begun in 1225, attempted to surpass even Amiens with a choir vault of 48 meters. In 1284, part of the vault collapsed. It was rebuilt, but the full cathedral was never completed. Beauvais stands as a magnificent fragment a reminder that the cathedral builders were pushing at the very limits of what stone and mortar could achieve.

Who built the cathedrals?

The great cathedrals were collective enterprises on a scale that is difficult to comprehend today. A major cathedral might take fifty to a hundred years to build, spanning multiple generations of workers, patrons, and architects.

The master builders

At the apex of the building team stood the master mason — what we would today call the architect. Figures like Jean d’Orbais and Villard de Honnecourt left traces in the historical record, but many remain anonymous. These men were not merely craftsmen; they were engineers, geometricians, and problem-solvers of the highest order, working without modern mathematics or computing to create structures that have stood for eight centuries.

The labor force

Beneath the master mason worked an army of skilled and unskilled laborers: stone cutters, carpenters, glass makers, sculptors, mortar mixers, and simple haulers. A major construction site might employ hundreds of workers at peak activity. Entire communities mobilized chronicles record townspeople, including women and children, joining in the effort to haul materials.

The financing

Building a cathedral was ruinously expensive. Funding came from a complex mix of sources: episcopal revenues, royal grants, indulgences, relics collections (the cult of relics could attract enormous donations), and contributions from guilds and wealthy families. The economic impact was enormous cathedrals stimulated trade, attracted pilgrims, and drove technological innovation.

A french invention, exported to the world

It is worth pausing to appreciate the scale of France’s achievement. Gothic architecture was not just a French style it was a French *invention* that transformed the built environment across the entire continent.

From France, Gothic spread rapidly: to England (Canterbury, Lincoln, Salisbury), to the Holy Roman Empire (Cologne, Strasbourg), to Spain (Burgos, León, Toledo), to Italy (Milan, Siena), and even to the Crusader states in the Levant. Each region adapted the Gothic vocabulary to local tastes and traditions, but the fundamental grammar pointed arches, ribbed vaults, flying buttresses, walls of glass — remained unmistakably French in origin.

The word “Gothic” itself is a misnomer, coined dismissively by Renaissance Italians who associated the style with the “barbarous” Goths. The medieval builders themselves called it opus francigenum “French work.” They knew exactly where it came from.

The spiritual and intellectual revolution

Gothic architecture was more than an engineering triumph. It was an expression of a new way of thinking about the relationship between the material and the divine, between human creativity and God’s glory.

The great cathedrals were encyclopedias in stone and glass. Their sculptural programs told the stories of the Bible, the lives of saints, the labors of the months, and the liberal arts. Their stained-glass windows were “the Bible of the poor,” communicating complex theological narratives to a largely illiterate population through images of breathtaking beauty.

At the same time, the cathedral-building era coincided with the birth of the universities Paris’s own university emerged in the early thirteenth century, within sight of Notre-Dame. The same intellectual energy that produced scholastic philosophy and the great theological summae also drove the quest for structural perfection in stone. Gothic architecture and the medieval university were twin expressions of the same French genius for synthesis, ambition, and the pursuit of knowledge.

Discover french civilization with the CCFS

The Gothic cathedrals are more than historical monuments they are living witnesses to French civilization at its most ambitious and creative. To walk through Notre-Dame, Chartres, or Reims is to enter a world where faith, art, engineering, and intellect converged to produce works of enduring beauty.

At the Cours de civilisation française de la Sorbonne (CCFS), we believe that understanding French culture means engaging with these great works not as distant relics, but as keys to understanding the French spirit. Our French Civilization courses offer students from around the world the chance to explore the art, architecture, history, and ideas that define France, all while perfecting their command of the French language.

Come study in Paris, where the Gothic revolution began, and discover for yourself why France’s cathedral builders continue to inspire awe nearly a thousand years later.